I Learned Every Way to Multiply Two Numbers

In 2019, we apparently perfected multiplication. This news may be as shocking to you as it was to me. There’s more than one way to multiply?

There is indeed. In fact, there are about a dozen or so distinct ways of multiplication taught across the world. They boil down to 5 methods, since many approaches use different aesthetics but the same core principle. This week, I endeavored to learn every way to multiply numbers.

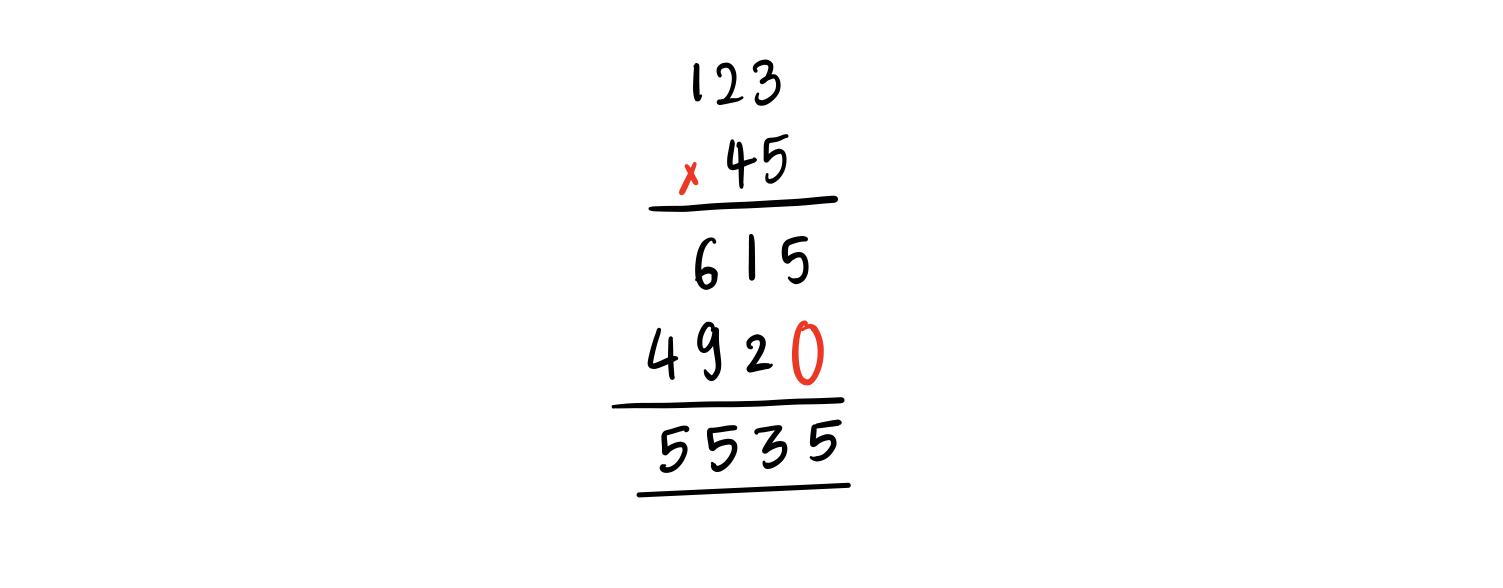

Method 1: The Long Multiplication#

This is the multiplication most of us are familiar with. Mathematically, it can be expressed as: $$ 45 \cdot 123 = 45 \cdot 100 + 45 \cdot 20 + 45 \cdot 3 $$ More generally, $$x \cdot y = x \sum_{i=0}^{n–1}yi10^i = \sum{i=0}^{n–1}(x\cdot y_i)10^i$$

Some of you may have learned this using the “grid method”, and yet another group may have used the “lattice method”. The same principle underlies all of them. I learned this method in the form of a vertical table.

A quick analysis of the efficiency of this algorithm reveals a bound of $O(n^2)$. We can try to do better.

A quick analysis of the efficiency of this algorithm reveals a bound of $O(n^2)$. We can try to do better.

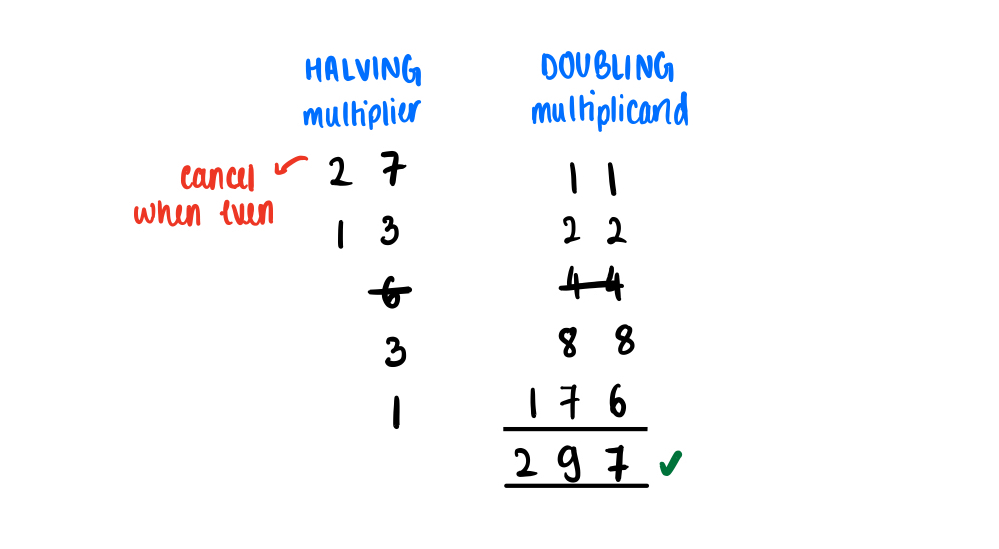

Method 2: Peasant Multiplication#

This method has historically been used by “peasants” who have not memorized multiplication tables. Mechanically, the method includes halving the multiplier, doubling the multiplicand, canceling out every even instance of the multiplier, then adding the multiplicands.

Proof#

Collorary: All numbers can be expressed as a sum of powers of two. (Proof)

Let multiplicand $x$ and multiplier $y$ such that $$y = \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} b_i \cdot 2^i, \text{ } b_i = 0 \text{ or } 1$$ Using our example above, $$27 = 1 \cdot 2^4 + 1 \cdot 2^3 + 0 \cdot 2^2 + 1 \cdot 2^1 + 1 \cdot 2^0$$ $$27 \cdot 11 = (2^4 + 2^3 + 2 + 1) \cdot 11 = 11 + 22 + 88 + 176 = 297 \checkmark$$

This algorithm